Running Towards Virtue | Prudence

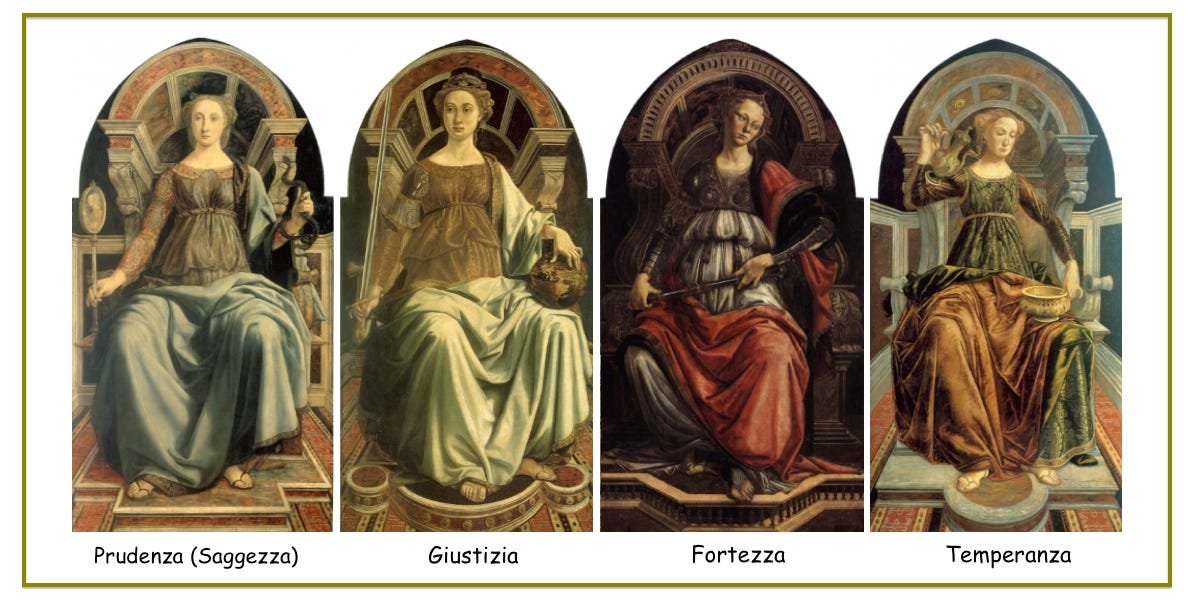

Prudence is the charioteer of all the other moral virtues

In our last newsletter, we spoke about what it means to be free and we distinguished between an Enlightenment view of freedom (freedom of indifference) and that of the Christian and Thomistic idea of freedom (freedom for excellence or virtue).

Now we get to discuss growing in freedom and how the moral or cardinal virtues help us do that.

For the purposes of this newsletter, we’re going to focus on the virtue of Prudence which has commonly been called the “charioteer of the virtues” because of how it directs and commands the other virtues.

Prudence is the virtue by which we “see” rightly and is the most necessary of the virtues. Prudence means we see reality as it is and not as we might like it to be.

It would not be incorrect to say that without Prudence we cannot really engage in any of the other virtues, at least not fully! A man or woman could not be just to his neighbor or temperate or courageous in his desires and actions if he did not see reality rightly, aka if he or she did not have Prudence.

It would seem than that omnis virtus moralis debet esse prudens—All virtue is necessarily prudent.

By Prudence we judge accurately what is morally good, acceptable, and beautiful in particular circumstances and then we act.

Prudence can sometimes be thought of as caution or even timidity but that concept fails to give Prudence it’s full significance. Contemporary and modern minds might very well consider it prudent to avoid the situation of having to be courageous or that it is prudent to cleverly avoid committing oneself.

I am reminded of the musical Hamilton where Aaron Burr famously hides his real thoughts and opinions and dissembles to get what he wants, namely: power, influence, and worldly significance.

I might call Aaron Burr clever but I would certainly not call him prudent, at least not according to the Catholic and Thomistic tradition.

The Catechism, quoting our Dominican brother St. Thomas Aquinas makes this clear when it states in CCC 1806:

Prudence is "right reason in action," writes St. Thomas Aquinas, following Aristotle. It is not to be confused with timidity or fear, nor with duplicity or dissimulation. It is called auriga virtutum (the charioteer of the virtues); it guides the other virtues by setting rule and measure. It is prudence that immediately guides the judgment of conscience. the prudent man determines and directs his conduct in accordance with this judgment. With the help of this virtue we apply moral principles to particular cases without error and overcome doubts about the good to achieve and the evil to avoid.

Prudence and the elements of Prudence

Deliberation

Depending on the complexity of the situation in question, one has to consider the goal in mind and the means of attaining that goal. The prudent soul always considers the path set before him or her before setting out. This involves knowledge of principles, Church teaching, etc.

Judgement

After the stage of deliberation comes judgement. Once deliberation is finished, a judgement is made concerning the proper action in this particular matter. This is quite simple: either we are attracted to the action and the goal or we are repulsed.

Execution

And after both deliberation and judgment comes execution. Prudence is always oriented towards a particular action. The person who claims to be prudent but fails to act or allows fear to prevent him or her from acting, is not truly prudent at all. At this point, we commit to our goal and the action we have determined as the best means of achieving it. If you figure out the proper action, but then fail to do it, what would be the benefit?

Regardless of where we are in the spiritual life, whether we are beginners or more advanced souls, we can grow in this virtue through some simple exercises and habits.

Prudence demands that we deliberate and consider each decision, not waiting until the last minute to decide, but engaging in reflection before acting.

What does memory, memoria, tell us about this situation based on our past experiences and knowledge? Have we engaged in this action or behavior before? What was the result of that action? Did this behavior cause our freedom injury or assist us in growing in our full humanity?

At the same time, the prudent man or woman also must practice docilitas, or docility. We do not possess all knowledge, shocking I know!

Therefore we must be open and able to take advice. A closed mind or someone who already believes they have all the answers, has abandoned prudence for pride and that is a sad and sorry trade indeed.

Finally, we come to the need for solertia which roughly translates to “perfected ability.” With this trait we can swiftly, and with a rightly ordered vision, make decisions for the good and avoid the pitfalls of injustice, cowardice or intemperance.

We are able to with solertia respond nimbly but reflectively to situations and not to be caught hesitating to the point of cowardice or indecision.

While there is much more we might say, we should sum up briefly what we know of Prudence so far and offer a few suggestions for both action and study.

Prudence enables us to see rightly in a concrete situation and to turn this sight into concrete action. Take your time in consideration but once you reach a judgment, act decisively.

Once you act, commit to the action and follow through. Think of it as though you were trying to change your golf swing in mid-swing, if you do that you’re going to slice the ball and mess up your stroke and then you are most definitely “in the rough.”

Finally, recognize that you will never reach a point of absolute certainty. Prudence and knowledge never reach the point of 100 percent certainty.

The Thomist philosopher Josef Pieper makes the remark that the “prudent man does not deceive himself with false certainties."

Human life on earth does not perfectly conform to the logic and certainty of mathematics, and so if you’re waiting for 100 percent certainty, you’ll never do anything at all.

A key, and final, question for our reflection, as we consider what is to be prudent, is to consider our ultimate Hope: the Beatific Vision of Heaven.

As we consider a decision we should ask ourselves: What does this profit me toward eternal life?

We may not reach complete and perfect surety, but if we are honestly oriented towards this goal, God shall assist us in seeing and acting rightly so that we might achieve Heaven through His Grace.

And that is truly the goal of all our lives.

For further reading on the topic of Prudence: